- Home

- Miranda July

The First Bad Man: A Novel Page 13

The First Bad Man: A Novel Read online

Page 13

“It probably still fits you.”

“I don’t think so.” An older, blue-blooded woman with white hair and real pearl earrings could have been elegant in it. Anyone younger or poorer would look like a soldier from one of those countries where women hold automatic weapons. I pulled out my pin-striped men’s shirt. She took it into the bathroom with her but when she came out she was still wearing her tank top.

“It’s not my style,” she said, handing it back.

“Does it feel natural to you?” I asked. “To be pregnant?”

“It is natural,” she said. “It’s the medical establishment that makes it unnatural.”

Her friend Kelly had given birth at home in a bathtub. Same with her friend Desia. There was a whole group of girls in Ojai who had put their babies up for adoption through a Christian organization called Philomena Family Services. All of them home-birthed with midwives.

“But here, in LA, the hospitals are really good, so you don’t need to do that.”

“You don’t need to tell me what I don’t need to do,” she said, narrowing her eyes. For a split second I thought she was going to push me against a wall. But no, of course not. That was all over.

EVERYONE AT OPEN PALM KNEW and thought it was big of me to take her in like this.

“She was already in—I just didn’t kick her out.”

“But you know what I mean,” said Jim. “Risking your job.” My job was in no danger; Suzanne and Carl routinely sniffed out news of Clee from my coworkers. After each prenatal checkup I made sure to circulate the update. Everyone assumed I knew who the father was, but I didn’t. I didn’t know anything. It seemed impossible to broach the subject without also recalling our past, the scenarios, my betrayal. The unspoken agreement was we wouldn’t look back.

In the middle of the second trimester I saw Phillip. He was parking his Land Rover just as I was leaving the office. I ducked into a doorway and waited for twenty minutes while he sat in his car, talking on the phone. Probably to Kirsten. I didn’t want to think about it. Everything was in delicate balance and it needed to stay that way. When I finally walked to my car my legs were shaking and I was drenched in a foul sweat.

Each night I listened as she stumbled to the bathroom, bumping into the doorway and then hitting it again on the way back. It was torture.

Finally one night I yelled out from bed. “Careful!”

She stopped abruptly and through my half-open door I watched her stand in the moonlight and touch the swell of her stomach with a look of shock, as if the pregnancy had just come upon her right then.

“Was it Keith?” I called out.

She didn’t move. I couldn’t tell if she was awake or had fallen back asleep, still standing.

“Was it one of the men from the party? Did it happen at the party?”

“No,” she said huskily. “It happened at his place.”

He had a place called his place and it happened there and it was sex. This was both more and less than I wanted to know.

“It’s a nightmare,” she said, holding her stomach.

“Is it?” I was desperate to know more. She lurched back to bed. “Is it?” I cried again, but she was done, already half-asleep. It could only be a nightmare, someone growing inside you who you hoped never to see the face of.

IN THE MORNING I TRIED for a more hard-nosed approach.

“I think for safety’s sake I should know who the father is. What if something happens to you? I’m responsible.”

She looked surprised, almost slightly moved.

“I don’t want him to know about it. He’s not a good person,” she said quietly.

“Why would you do that with someone who’s not a good person?”

“I don’t know.”

“If it was nonconsensual then we should call the police.”

“It wasn’t nonconsensual. He’s just not the type of person I usually go for.”

How did they form the consensus? Did they vote? Did everyone in favor say aye. Aye, aye, aye. I went into the ironing room and returned with a pen, a piece of paper, and an envelope.

“I won’t open it, I promise.”

She went into the bathroom to write the name. When she came out she slid the envelope between two books in the bookshelf and then carefully placed the tab from a soda can in front of the books. As if it would be impossible to re-create the position of a soda can tab.

I ACTED QUICKLY, SETTING UP an emergency therapy appointment before Clee had a chance to think harder about trusting me. Once I was behind the pee screen I asked Ruth-Anne to look in my purse.

“There’s a sealed envelope and an open empty envelope,” I said. “Open the sealed one.”

“Rip it open?”

“Open it the way you would normally open an envelope.”

A clumsy ripping sound.

“Okay. It’s open.”

“Is there a name on a piece of paper?”

“Yes, do you want me to read it to you?”

“No, no. It’s a man’s name?”

“Yes.”

“Okay.” I shut my eyes as if he was standing on the other side of the screen. “Write that name down.”

“On what?”

“On anything, on an appointment card.”

“Okay. I’m done.”

“Already?” It was a short name. It wasn’t an unusual, long, foreign name with many accents and umlauts that one would have to double-check. “Okay, now put the paper back in the unsealed envelope and seal it.”

There was a complicated rustling of papers and some banging.

“What are you doing?”

“Nothing. I dropped them. I hit my head on the table picking them up.”

“Are you okay?”

“A little dizzy, actually.”

“Is the envelope sealed?”

“Yes, now it is.”

“Good, now put the envelope in my purse and put the card with the name somewhere safe that I can’t see.”

She laughed.

“What’s funny?”

“Nothing. I hid it in a really good place.”

“It’s done then? I’m gonna come out. Okay?”

“Yes.”

Ruth-Anne stood wide-eyed and smiling with her hands behind her back. The envelope was in many torn pieces strewn all over the rug. When you get something notarized, there is a dignified feeling about the proceedings, even if the notary is just a stationery store clerk. I had expected this to be more like that.

“What’s behind your back?”

She opened her empty hands in front of herself. Now she was rolling her eyeballs to the side of the room in a strange way.

“What are you doing? Why are you looking over there?”

Her eyes jumped back. She pressed her lips together, raised her eyebrows and shrugged.

“Is the card over there?”

She shrugged again.

“I don’t want to know where it is.” I sat down on the couch. “This is probably unethical.” I waited for her to draw me out. There were still ten minutes left in the session. Ruth-Anne sat down and rubbed her chin, holding her elbow and nodding significantly. She seemed to be acting out the role of a therapist in a mocking way, like a child pretending to be a therapist. “I don’t want to break my promise to Clee,” I continued, “but I also want the option of knowing. What if there’s a problem? What if we need his medical history? Do you think that’s wrong?”

Something slid down the wall. Ruth-Anne’s eyes grew wide but she made a great show of ignoring it.

“Was that the card?”

She nodded vigorously. She had hidden it behind one of her diplomas. It now lay on the floor. I averted my eyes.

“It doesn’t need to be hidden like an Easter egg. Just put it in your desk drawer

.” She leapt to the card and rushed it not to her desk but out the door to the receptionist’s desk, slamming the drawer as if the card was a rascally character, prone to escape.

“Where were we?” she said, returning breathlessly and folding herself back into the therapist pose.

“I asked if you thought this was wrong.”

“And I’ve been telling you.” She was suddenly herself again, dignified and intelligent.

“What do you mean?”

“You wanted to play like a child, so we played.”

I slumped back into the couch and my eyes ached with dry tears. This is why she was so good, always finding a way to take it right to the edge.

“You can throw out the card,” I said, winded.

“I’ll keep it there as long as you want. Our lives are filled with childish pranks, Cheryl. Don’t run from your playing, just notice it: ‘Oh, I see that I want to play like a little girl. Why? Why do I want to be a little girl?’ ”

I hoped she wouldn’t make me answer this question.

“Have you ever considered being birthed for a second time?” she asked.

“Like born again?”

“Rebirthing. Dr. Broyard and I thought it might be a good idea.”

“Dr. Broyard? You talk to him about me?”

She nodded.

“What about patient confidentiality?”

“That doesn’t apply to other doctors. Would a pulmonologist withhold information from a neurologist?”

“Oh, right.” I hadn’t realized I was such a serious case.

“We’re certified”—she gestured to a certificate on her wall—“to work as a team.”

I squinted at the certificate. TRANSCENDENTAL REBIRTHING MASTERS CERTIFICATION II.

“Do you really think it’s necessary?”

“Necessary? No. All that’s necessary is that you eat enough to survive. Were you happy in the womb?”

“I don’t know.”

“After a session with us you will know. You’ll remember being a single cell and then a blastula, violently expanding and contracting.” She grimaced, contracting her upper body with a tortured shiver and then groaning with expansion. “All that upheaval is inside you. It’s a heavy load for a little girl.”

I pictured lying on the floor with Ruth-Anne’s groin against the top of my head. “Why does Dr. Broyard need to be there?”

“Good question. The baby may have consciousness even before fertilization, as two separate animals—the sperm and egg. So we like to begin there.”

“With fertilization?”

“It’s just a ritual symbolizing fertilization, of course. Dr. Broyard would play the role of the spermatozoa and I would play the ovum. The waiting room”—she pointed to the waiting room—“becomes the uterus and you come through that door to be born.”

I looked at the door.

“He’s here with his wife this weekend, a special trip. How’s Sunday at three?”

“Okay.”

She glanced at the clock; we were out of time.

“Should I—?” I pointed to the scraps of paper on the floor.

“Thank you.” She checked her phone messages while I knelt down and gathered the pieces of envelope. I carried them out with me, not wanting to clutter her wastepaper basket.

After slipping the envelope back between the books and repositioning the soda can tab, I clicked back through Grobaby.com. Nothing about the blastula expanding and contracting. I stared at a cartoon fetus, biting my fingernail. This website was not a how-to guide. If the thing in Clee was in any way relying on my narration, there would be major gaps in its development. I saw a lazy, text-messaging, gum-chewing embryo, halfheartedly forming vital organs.

Embryogenesis arrived the next day; I splurged on expedited shipping. Its nine hundred and twenty-eight pages weren’t neatly divided into weeks, so it seemed safest to start at the beginning. I waited until Clee was done eating her kale and tempeh. She settled on the couch and I cleared my throat.

“ ‘Millions of spermatozoa travel in a great stream upwards through the uterus and into the Fallopian tubes—’ ”

Clee held up her hand. “Whoa. I don’t know if I want to hear this.”

“It already happened, I’m just recapping.”

“Do I have to listen?” She picked up her phone and headphones.

“Music might be confusing—it has to hear my voice.”

“But my head is way up here.”

She scrolled through her phone, found something with a thumping beat, and nodded at me to go on.

“ ‘The successful sperm,’ ” I orated, leaning toward her round belly, “ ‘merges with the egg and its nucleus fuses with the egg’s nucleus to form a new nucleus. With the fusion of their membranes and nuclei the gametes become one cell, a zygote.’ ” I could see it so clearly, the zygote—shiny and bulbous, filled with the electric memory of being two but now damned with the eternal loneliness of being just one. The sorrow that never goes away. Clee’s eyes were shut and her brow was sweaty; it wasn’t so long ago that she was two animals, Carl’s sperm and the ovum of Suzanne. And now the same thing was happening inside her, a new sorrowful creature was putting itself together as best it could.

The next morning I greeted my bosses with empathy; you would think a thing made of you would at least remain on speaking terms. Suzanne and Carl hadn’t heard from Clee in months. They sat as far away from me as possible, hands folded on the tabletop, a demonstration of civility. Jim smiled encouragingly; it was my first meeting of the board. Sarah took notes in my old chair, off to the side. I was formally welcomed and Phillip’s resignation was acknowledged.

“He’s not in great health,” Jim explained. “I vote for sending him a basket of mixed cheeses.” More likely he was too ashamed to show his face—and he should have been. Sixteen! A sixteen-year-old lover! When Suzanne argued against retirement benefits for Kristof and the rest of the warehouse staff, I found myself rising from my seat and jabbing my fist in the air like a person who knew something about unions. Taking Phillip’s place was wonderfully emboldening. When the vote fell in my favor, Suzanne mouthed “Touché.” She was studying my hair and clothes, as if I was someone new. I called Sarah Miss Sarah—like a servant. Suzanne laughed at this and asked Miss Sarah to bring us more coffee.

“You can sit down, Sarah,” Jim said. “Those two are just playing around.” I felt drunk with camaraderie. All these years I’d been looking for a friend, but Suzanne didn’t need a friend. A rival, though—that got her attention. When the meeting adjourned we both went to the staff kitchen and made cups of tea in silence. I waited for her to begin the conversation. I sipped. She sipped. After a while I realized this was the conversation; we were having it. She was giving me her blessing to care for her young and I was accepting the duty with humility. When Nakako came in, Suzanne walked away. For honor’s sake we would keep our distance.

RUTH-ANNE HAD WARNED AGAINST parking in the garage; there was no attendant on the weekend. I parked on the street. An elderly woman was cleaning the elevator as I rode up. She quickly Windexed the door when it shut behind me and then began cleaning the buttons, illuminating each one as she polished it, but politely focusing on the numbers above my floor.

The door was locked; I was early. I turned off my phone so it wouldn’t ring during the rebirthing. I sat in the hall. They were almost fifteen minutes late. Apparently they weren’t as professional about their side work—it was a more casual affair. Well, wasn’t I the fool for being exactly on time. After a while I remembered that the appointment was for three o’clock, not two o’clock; I was forty minutes early. I wandered around. No one worked on the weekends; the building was silent. Ruth-Anne’s office was at the end of a long corridor connected to another long corridor by a long corridor. An H formation. That was useful to know—I had never been total

ly clear about the floor plan of the building. How else can I use this time constructively? I asked myself. What can I do that I need to do anyway? I jogged back to the door, turned, jogged down each of the corridors—it was a terrific workout and no small distance. Thirty or forty H-reps probably equaled a mile, two hundred calories. After seven Hs I was covered in sweat and breathing heavily. As I jogged past the elevator it dinged. I accelerated, rounding the corner just as the doors swished apart.

“But the parking attendant doesn’t work on the weekends,” Ruth-Anne was saying. “He never has.” I ran past the door of her office and turned the corner. I needed a moment to catch my breath and wipe off my face.

“Oh no,” she said.

“What?”

“The key’s on my other ring. I just got a new fob and . . .”

“Jesus, Ruth-Anne.”

“Should I go back and get it?” Her voice was strangely high, like a mouse on a horse.

“By the time you get back here the session will be over.”

“You could work with her alone until I get back.”

“In the hallway? Just call her and cancel.”

It took her a moment to find my number in her phone.

“Straight to voice mail. She’s probably parking. I’m sure she’ll be up in a minute or two.”

My panting was hard to control and my nose was whistling. I should have gone farther down the hall but it was too risky to move now.

Dr. Broyard sighed. “This never really works out,” he said. It sounded like he was unwrapping a candy. Now something was clacking around in his mouth. “For one reason or another.”

“Rebirthing?”

“Just—these things you cook up so you can see me when I’m with my family.”

Ruth-Anne was silent. No one said anything for a long time; he started biting the candy.

“Is she even coming, or was this your plan, that we would stand in the hallway together and—what? Fuck? Is that what you want? Or you just want to blow me? Hump my leg like a dog?”

A confusing high-pitched noise seemed to descend from the vents, then broke into a mass of wet, convulsive gasps. Ruth-Anne was crying. “She’s coming, I promise. It’s a real session. It really is.”

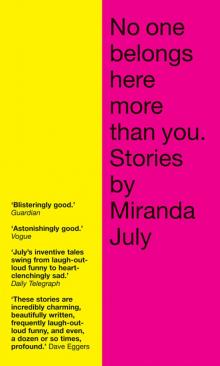

No One Belongs Here More Than You

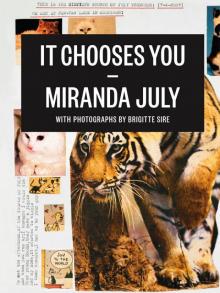

No One Belongs Here More Than You It Chooses You

It Chooses You The First Bad Man

The First Bad Man The First Bad Man: A Novel

The First Bad Man: A Novel